zdfb

Select date and time

E-tickets: Print at home or at the box office of the event if so specified. You will find more information in your booking confirmation email.

You can only select the category, and not the exact seats.

If you order 2 or 3 tickets: your seats will be next to each other.

If you order 4 or more tickets: your seats will be next to each other, or, if this is not possible, we will provide a combination of groups of seats (at least in pairs, for example 2+2 or 2+3).

Raymonda Variations is a flurry of ballet technique featuring a series of impressive solos at its center.

Balanchine admired Glazounov's score for the three-act ballet Raymonda, calling it "some of the finest ballet music we have." As a student in St. Petersburg, Balanchine danced in the Maryinsky Theatre production that had originally been choreographed by Marius Petipa.

In 1946, Balanchine and ballerina Alexandra Danilova mounted the full-length Raymonda for the Ballet Russe. Balanchine was not, however, enamored of the overly complicated storyline, and instead used excerpts from the score for several plotless works, including Pas de Dix, Cortège Hongrois, and Raymonda Variations.

Of this last one, Balanchine wrote:

To try to talk about these dances in any useful way outside the music is not possible; they do not have any literary content at all and of course have nothing to do with the story of the original ballet Raymonda. The music itself, its grand and generous manner, its joy and playfulness, was for me more than enough to carry the plot of the dances.

Raymonda was one of Petipa’s final, most successful ballets to be staged during the golden years of his career. The 1890s had seen some of the biggest highlights of Petipa’s career, which first emerged with the creation of The Sleeping Beauty. This late-era saw Petipa taking a slightly different step from what he had previously produced for the Saint Petersburg Imperial Ballet. He was now creating ballets that lacked dramatic plots and character development and were, instead, presenting new ballets that represented the grand spectacle. The ballet-féerie made its impact on the Imperial Ballet following the success of The Sleeping Beauty and materialized again in other ballets such as Cinderella and Bluebeard.

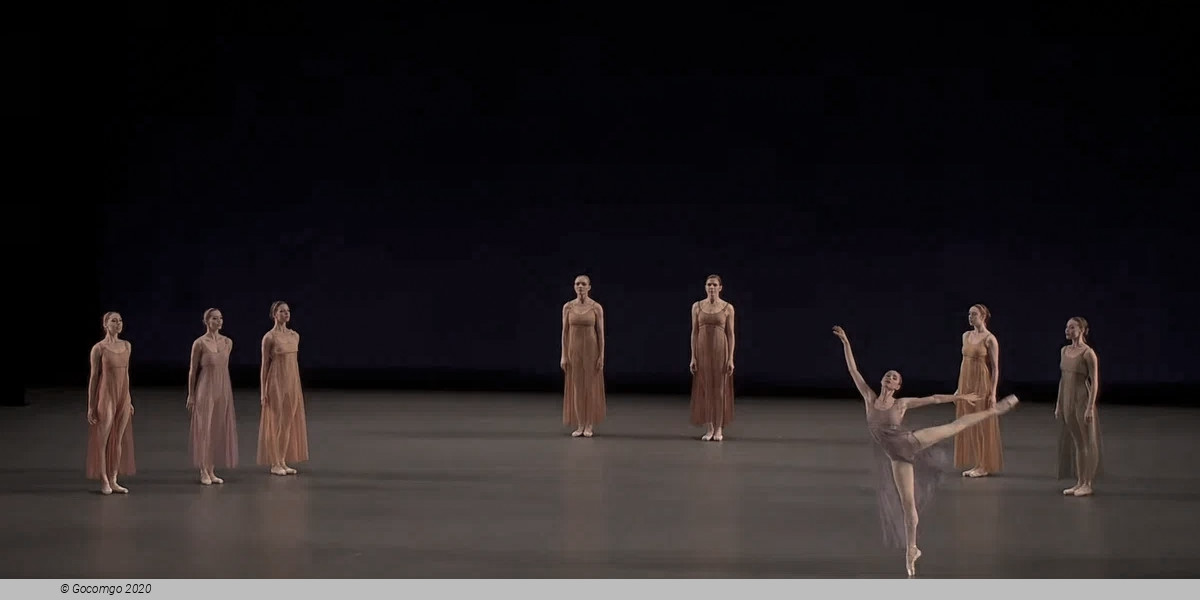

An all-female cast performs this dramatic and introspective piece, alluding to the earthy fervor and sculptural forms of Greek antiquity.

The first six sections of Antique Epigraphs are set to an orchestrated version of Six Epigraphes Antiques, music originally written as accompaniment for the prose poetry of Pierre Louÿs' Chanson de Bilitis, supposed translations of newly discovered autobiographical poetry of Sappho. The seventh section of the ballet is danced to Syrinx, a melody for unaccompanied flute.

Rooted in the court dances of 18th-century France, Le Tombeau de Couperin mesmerizes with its seamless patterns and symmetrical groupings of dancers.

In 1919 Maurice Ravel composed "Le Tombeau de Couperin” (“The Tomb of Couperin”), a commemorative suite for piano in six movements, in memory of six friends who died in World War I. He was inspired by the style of François Couperin, a French Baroque composer. In 1920, Ravel orchestrated four of the pieces, which make up the score for this ballet.

Balanchine choreographed Le Tombeau de Couperin for New York City Ballet’s 1975 Ravel Festival, and, like the composer, he incorporated French Baroque style and devices into a work with a modern sensibility. The eight couples are divided into left and right quadrilles, and each quadrille forms geometric patterns — diagonals, diamonds, squares — as they dance in unison or echo the movements of the opposite side.

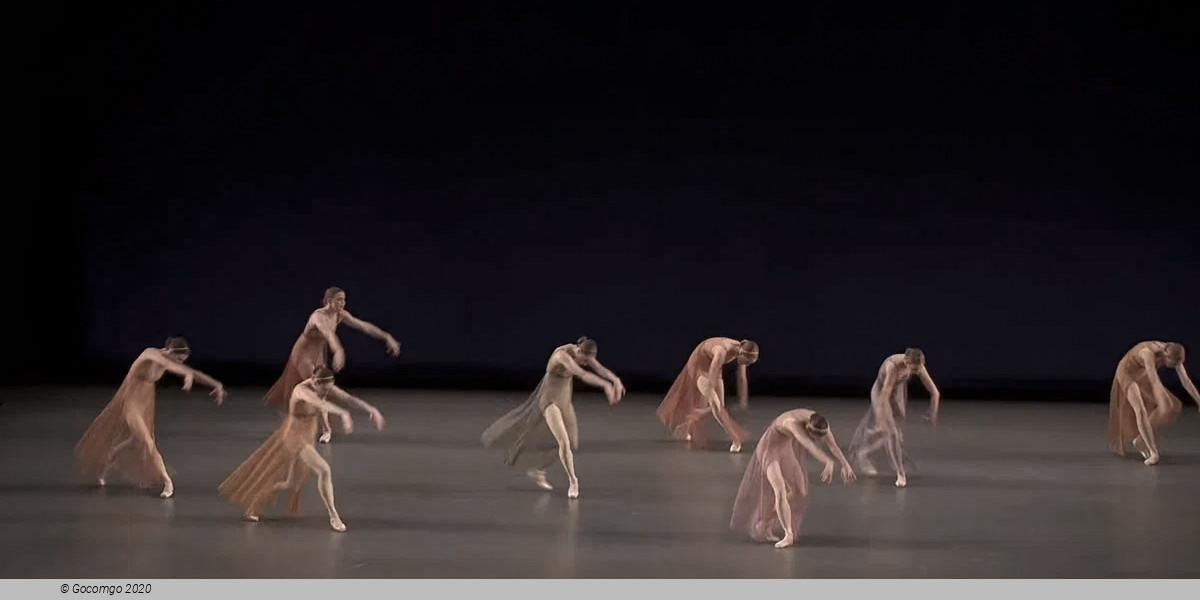

Requiring great energy, speed, and precision, the striking choreography in Kammermusik No. 2 echoes the intricacies of its modernist score with jagged lines and stylized gestures.

A ballet requiring great energy, speed, and precision, Kammermusik No. 2 has a complex structure that echoes the music; one of the dancers in the original cast likened it to a computer. The ballet is performed by two couples and an eight-man ensemble. The men, with their jagged lines and stylized gestures, dance to the music of the orchestra. The soloists, dancing to the complex passages for piano, are in counterpoint to the ensemble. The score is one of seven kammermusik pieces — the word “kammermusik” is German for “chamber music” — written by Hindemith between 1923 and 1933, when the composer turned to a neoclassical style evoking the Baroque.

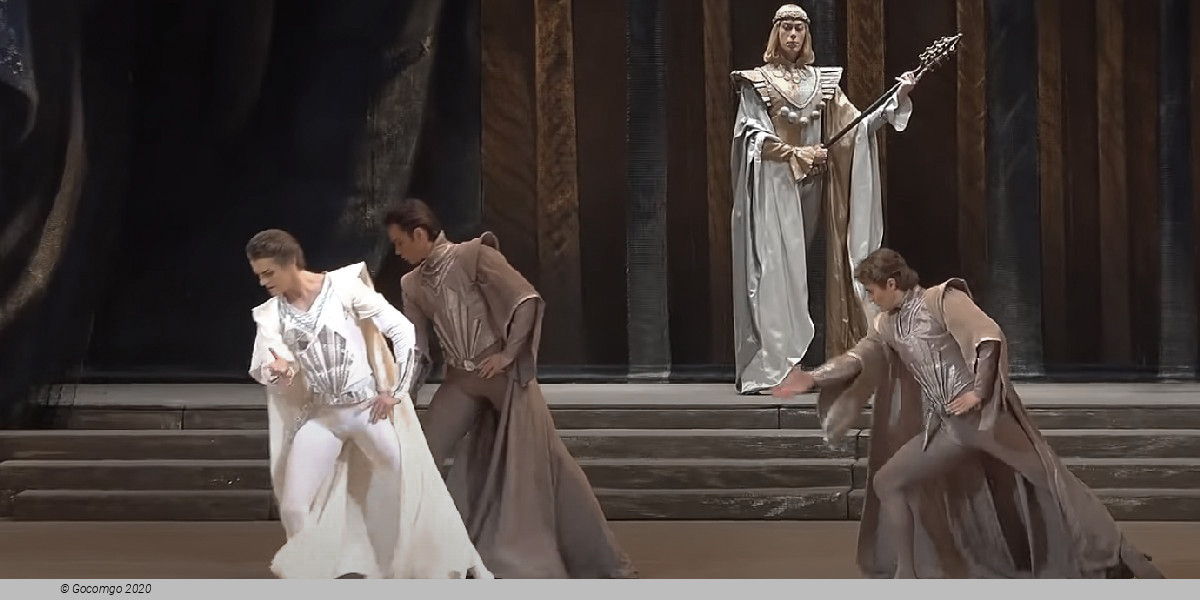

Raymonda is a ballet in three acts, four scenes with an apotheosis, choreographed by Marius Petipa to music by Alexander Glazunov, his Opus 57. First presented by the Imperial Ballet at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre on 19 January [O.S. 7 January] 1898 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The ballet was created especially for the benefit performance of the Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani, who created the title role. Among the ballet's most celebrated passages is the Pas classique hongrois (a.k.a. Raymonda Pas de dix) from the third act, which is often performed independently.

A ballet requiring great energy, speed, and precision, Kammermusik No. 2 has a complex structure which echoes that of the music; one of the dancers in the original cast likens it to a computer. The ballet is performed by two couples and an eight-man ensemble. The men, with their jagged lines and stylized gestures, dance to the music of the orchestra. The soloists, dancing to the complex passages for piano, are in counterpoint to the ensemble. There are pas de deux for the couples, duets for the women, and a fast duet for the male soloists. The score is one of seven kammermusik pieces — the word “kammermusik” is German for “chamber music” — written by Hindemith between 1923 and 1933, when the composer turned to a neoclassical style evoking the Baroque.

Act I

Scene 1: Raymonda's feast

At the castle of Doris, preparations are under way for the celebrations of the young countess Raymonda’s name day. Countess Sybille, her aunt, chides those who are present, including Raymonda's two friends Henrietta and Clémence, and the two troubadours Béranger and Bernard, for their idleness and their passion for dancing, telling them of the legendary White Lady, the protector of the castle, who warns the Doris household every time one of its members is in danger and casts punishment on those who do not fulfil their duties. The young people laugh at the countess’s superstitions and continue to celebrate. The seneschal of the Doris castle announces the arrival of a messenger, sent by Raymonda's fiancé, the noble crusader knight, Jean de Brienne, bearing a letter for his beloved. Raymonda rejoices when she reads that King Andrew II of Hungary, for whom Jean de Brienne has fought, is returning home in triumph and Jean de Brienne will arrive at the Doris castle the next day for their wedding. Suddenly, the celebrations are interrupted when the seneschal announces the arrival of an uninvited Saracen knight, Abderakhman and his entourage, who have stopped at the castle seeking shelter for the night. Captivated by Raymonda's beauty, Abderakhman falls in love with her at once and resolves to do anything to win her. The party lasts late into the night and, left alone and exhausted by the day, Raymonda lies down on a couch and falls asleep. As she sleeps, she begins to dream that the White Lady appears illuminated by the moonlight and, with an imperious gesture, orders Raymonda to follow her.

Scene 2: The Visions

The White Lady, without making a sound, advances along the terrace. Raymonda follows her in a state of unconsciousness. At a signal from the White Lady, the garden is wrapped in mist. A moment later, the mist vanishes and Jean de Brienne appears. Overjoyed, Raymonda runs into his arms and they are surrounded by glory, knights and celestial maidens. The garden is illuminated by a fantastic light and Raymonda expresses her joy to the White Lady, who interrupts her enthusiasm with a vision of what awaits her. Raymonda wants to return to her fiancé, but instead, she finds Abderakhman, who has taken Jean de Brienne's place. Abderakhman declares his passionate love for her, but Raymonda, though confused and upset, is quick to reject him. Imps and elves appear from everywhere surrounding Raymonda, who begs the White Lady to save her and Abderakhman tries to take Raymonda by force. Raymonda cries out and falls to the ground in a faint. The frightful vision disappears along with the White Lady.

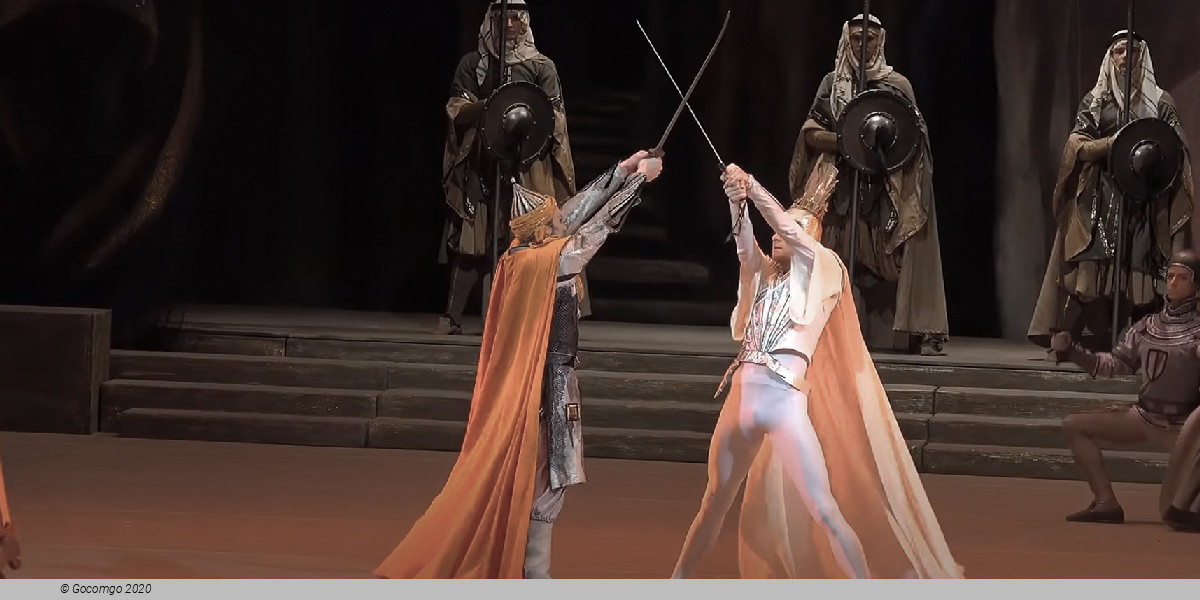

Act II

The Courtyard of the Castle

The feast in honour of Jean de Brienne's arrival is taking place. Raymonda welcomes her guests, but cannot hide her uneasiness caused by Jean de Brienne’s delay. Abderakhman approaches her repeatedly and reveals his passion for her, but remembering the warnings of the White Lady, Raymonda rejects him with contempt. Abderakhman becomes even more insistent and realises the only way to possess Raymonda is by force. He calls his slaves to dance for her, after which he summons his cup bearers and they pour a potion into everyone’s cup, causing all the guests to become drunk. Seizing his chance, Abderakhman grabs Raymonda in an attempt to abduct her, but luckily Jean de Brienne arrives just in time, accompanied by King Andrew II and his knights. Jean de Brienne saves Raymonda from the hands of the Saracens and tries to seize Abderakhman. The King commands the two rivals to put an end to the matter in a duel, during which the White Lady appears on the castle tower. Abderakhman is dazed and dies, slain by Jean de Brienne's sword. Raymonda joyfully embraces her fiancé and the two reaffirm their love as the King joins their hands.

Act III

The Wedding

Raymonda and Jean de Brienne are finally married and King Andrew II of Hungary gives the newly wedded couple his blessing. In his honour, everyone at court is dressed in Hungarian fashion and perform a range of Hungarian-style dances, ending in an Apotheosis where everyone comes together in a knightly tournament.

-