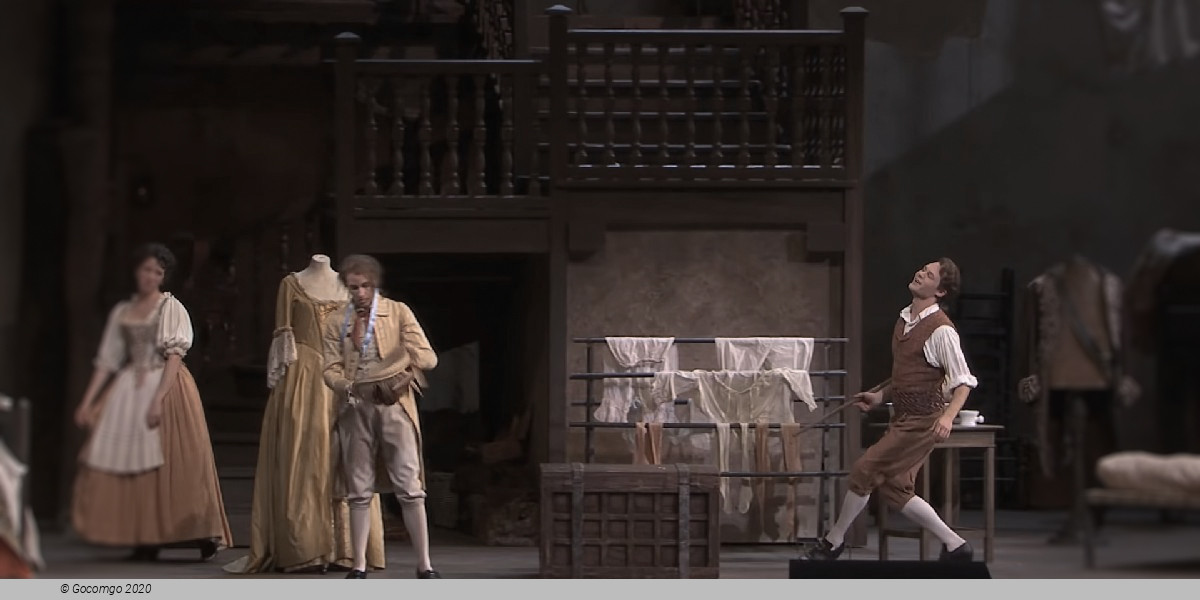

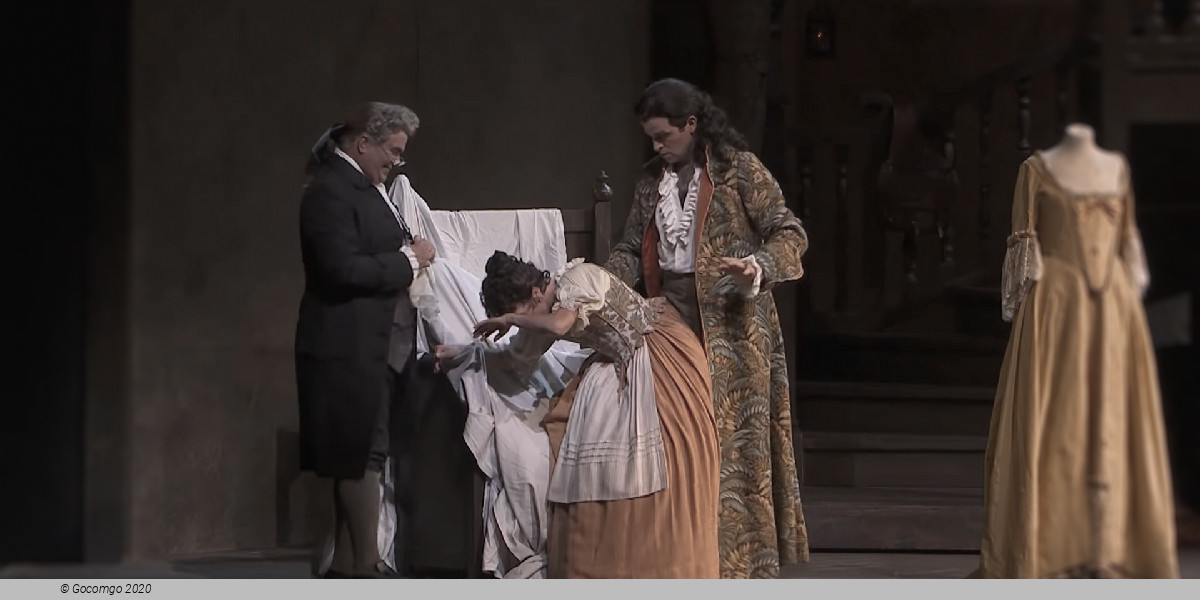

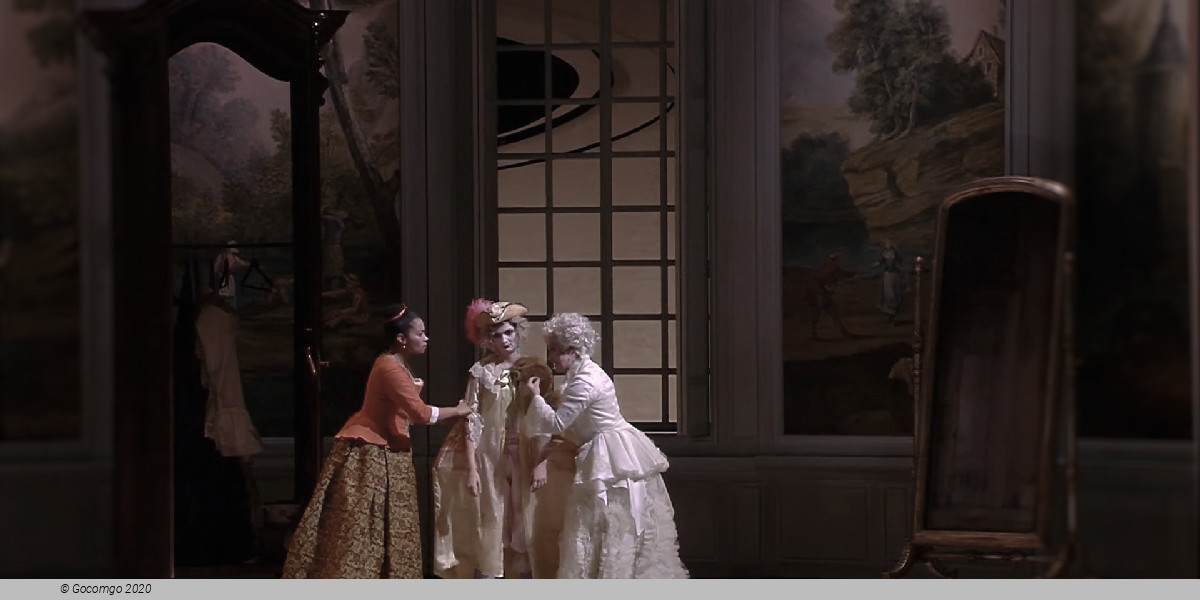

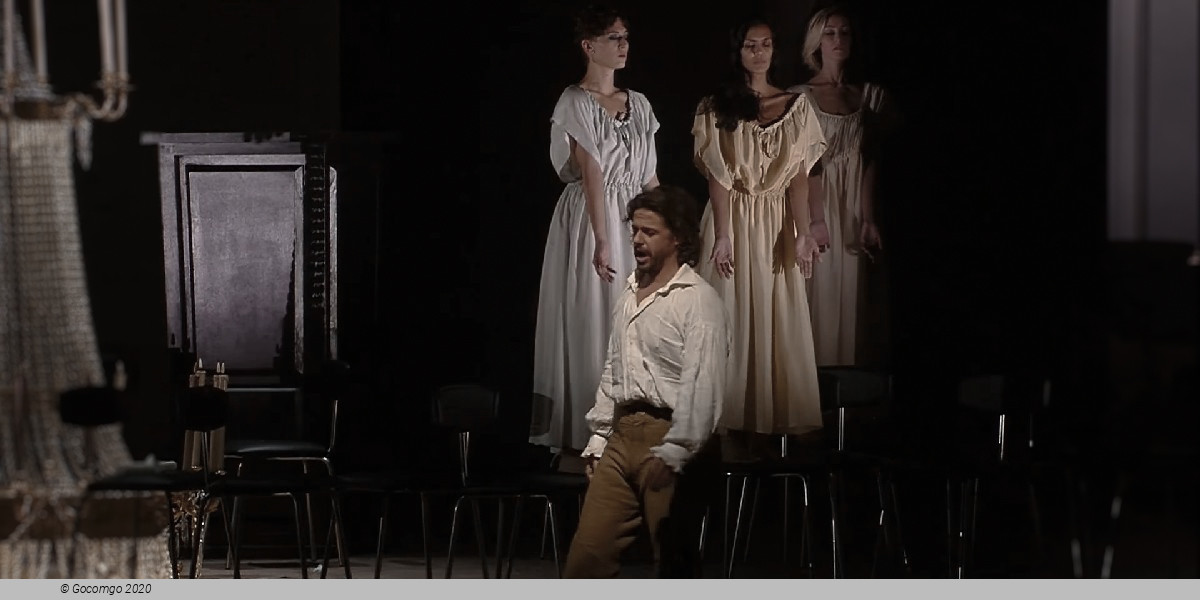

The Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie (or la Monnaie) in French, or The Koninklijke Muntschouwburg (or de Munt) in Dutch, is a leading opera house in Brussels. Both of its names translate as Royal Theatre of the Coin. Today the National Opera of Belgium, a federal institution, takes the name of the theatre in which it is housed - La Monnaie or De Munt refers both to the building as well as the opera company.

History

In the last three decades la Monnaie has reclaimed its place amongst the foremost opera houses in Europe thanks to the efforts of the successive directors Gerard Mortier and Bernard Foccroulle and music directors Sylvain Cambreling and Antonio Pappano.

The current edifice is the third theatre on the site. The façade dates from 1818 with major alterations made in 1856 and 1986. The foyer and auditorium date from 1856, but almost every other element of the present building was extensively renovated in the 1980s.

The theatre of Gio-Paolo Bombarda, 1700 to 1818

The first permanent public theatre for opera performances of the court and city of Brussels was built between 1695 and 1700 by the Venetian architects Paolo and Pietro Bezzi, as part of a rebuilding plan following the bombardment of Brussels. It was built on the site of a building that had served to mint coins. The name of this site la Monnaie ("the Mint") remained attached to the theatre for the centuries to come. The construction of the theatre had been ordered by Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, at that time Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands. The Elector had charged his "trésorier", the Italian Gio-Paolo Bombarda, with the task of financing and supervising the enterprise. The date of the first performance in 1700 remains unknown.

The first performance mentioned in the local newspaper was Jean-Baptiste Lully's, Atys, which was given on 19 November 1700. The French operatic repertoire would dominate the Brussels stage throughout the following century, although performances of Venetian operas and other non-French repertoire were performed on a regular basis. Until the middle of the 19th century, plays were performed along with opera, ballet and concerts.

By the 18th century la Monnaie was considered the second French-speaking stage after the most prominent theatres in Paris. Under the rule of Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, who acted as a very generous patron of the arts, the theatre greatly flourished. At that time it housed an opera company, a ballet and an orchestra. The splendour of the performances diminished during the last years of the Austrian rule, due to the severe politics of the Austrian Emperor Joseph II.

After 1795, when the French revolutionary forces occupied the Belgian provinces, the theatre became a French Departmental institution.

Amongst other cuts in its expenses, the theatre had to abolish its Corps de Ballet. During this period many famous French actors and singers gave regular performances in the theatre during their tour of the provinces of the Empire. Still a consul, Napoleon on his visit to Brussels judged the old theatre too dilapidated for one of the most prestigious cities of his Empire. He ordered plans to replace the old building by a new and more monumental edifice, but nothing was done during the Napoleonic rule. Finally, the plans were carried out under the auspices of the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Bombarda building was demolished in 1818.

The theatre of Louis Damesme, 1818 to 1855

The old theatre was replaced by a new Neo-classical building designed by the French architect Louis Damesme. Unlike the Bombarda building, which was situated along the street and completely surrounded by other buildings, the new theatre was placed in the middle of a newly constructed square. This gave it a more monumental appearance, but it was primarily the result of safety concerns since it was more accessible to firemen, reducing the chance that fire would spread to surrounding buildings. The new auditorium was inaugurated on 25 May 1819 with the opera La Caravane du Caire by the Belgian composer André Ernest Modeste Grétry.

As the most important French theatre of the newly established United Kingdom of the Netherlands, la Monnaie had national and international significance. The theatre came under the supervision of the city of Brussels, which had the right to appoint a director charged with the management its management. In this period famous actors like François Joseph Talma and singers like Maria Malibran performed at la Monnaie. The Corps de Ballet was reintroduced and came under the supervision of the dancer and choreographer Jean-Antoine Petipa, father of the famous Marius Petipa.

La Monnaie would play a prominent role in the formation of the Kingdom of Belgium. Daniel Auber's opera La Muette de Portici was scheduled in August 1830 after it had been banned from the stage by King William I, fearing its inciting content. At a performance of this opera on the evening of 25 August 1830, a riot broke out which became the signal for the Belgian Revolution and which led to Belgian independence. The Damesme building continued to serve for more than two decades as Belgium's principal theatre and opera house until it burnt to the ground on 21 January 1855 leaving only the outside walls and portico.

The theatre of Joseph Poelaert, since 1856

After the fire of January 1855, the theatre was reconstructed after the designs of Joseph Poelaert within a period of fourteen months. The auditorium (with 1,200 seats) and the foyer were decorated in a then-popular Eclectic Style; a mixture of Neo-Baroque, Neo-Rococo and Neo-Renaissance Styles. The lavish decoration made excessive use of gilded "carton-pierre" decorations and sculptures, red velvet and brocade. The auditorium was lit by the huge crystal chandelier that today still hangs in the centre of the domed ceiling. It is made of gilded bronze and venetian crystals. The original dome painting – representing "Belgium Protecting the Arts" – was painted in the Parisian workshop of François-Joseph Nolau (Paris 1804-1883) and Auguste Alfred Rubé (Paris, 1815-1899), two famous decorators of the Parisian Opera House. In 1887 this dome painting was completely repainted by Auguste-Alfred Rubé (Paris, 1815-1899) himself and his new associate Philippe-Marie Chaperon (Paris, 1826–1907), because it was mostly tainted by the CO2 emissions from the chandelier. This dome painting stayed untouched until 1985, when it was taken down during extensive rebuilding activities and replaced by a bad copy, painted by the Belgian painter Xavier Crolls. From 1988 until 1998 the dome painting of Rubé and Chaperon was in restoration. In 1999, it was reinstated and decorates today one of the most beautiful opera houses of Europe. The sober whitewashed exterior we see today was done many decades later. Poelaert never intended to whitewash these outer walls. In 1856, the exterior did not have any whitewashing at all, which is proved by many photographs of that time.

The new Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie opened on 25 March 1856 with Fromental Halévy’s Jaguarita l'Indienne. In the middle of the 19th century the repertoire was dominated by the popular French composers such as Halévy, Daniel Auber, and Giacomo Meyerbeer, and the Italian composers, Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, Vincenzo Bellini and Giuseppe Verdi who had considerable success in Paris.

The opera house in the 20th century

Renovations on the Poelaert building were required shortly after the opening due to faulty foundation work; the early 20th century saw an additional story added; and in the 1950s, a new stage building was added. By 1985 it was determined that complete renovation was needed. Features such as raising the roofline by 4 metres and scooping out the stage building area - in addition to creating a steel frame to strengthen the load-bearing walls and increasing backstage space - characterized this two-year project. However, the red and gold auditorium remained basically the same. The canvas of the ceiling painting was temporarily removed for restoration and only put back in 1999. It was temporarily replaced by a copy in much brighter colors that was painted directly on the stucco ceiling.

The entrance hall and the grand staircase underwent a radical makeover, although original features such as the monument by Belgian sculptor Paul Du Bois honouring manager and musical director Dupont (1910), and a number of monumental paintings (1907-1933) by Emile Fabry were preserved. The Liège architect Charles Vandenhove created a new architectural concept for the entrance in 1985-86. He asked two American artists to make a contribution: Sol LeWitt designed a fan-shaped floor in black and white marble, while Sam Francis painted a triptych mounted to the ceiling. Vandenhove also designed a new interior decoration for the Salon Royal, a reception room connected to the Royal box. For this project he collaborated with the French artist Daniel Buren.

Now seating 1,125, the renovated opera house was inaugurated on 12 November 1986 with a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

In 1998 the major part of the vacant Vanderborght Department Store building (c. 20,000 m2) and a neo-classical mansion, both situated directly behind the opera house, were acquired by la Monnaie. The edifices were renovated and adapted to house the technical and administrative facilities of la Monnaie, previously spread all over the city. The building also contains large rehearsal halls for opera, the Malibran, and orchestra, the Fiocco. They can also be adapted for presenting public performances.

La Monnaie in the 21st century

The opera house was renovated again from May 2015 to September 2017: the stage was levelled, a new fly system was put in place and two scene lifts were installed. This allowed the opera house to stage more technically-demanding productions. Although most of the renovations took place backstage, the opera house used this opportunity to replace all of its worn out seats with new velour seats.

Dadaocheng Theater

No. 21, Section 1, Dihua St, Datong District

Dadaocheng Theatre is a small theater that focuses on the performance and development of traditional Taiwanese opera. Originally, it occupied one floor of Yongle Tower; it now has expanded to two floors, with a performance hall that can hold 506 audience members.

5, Place de la Monnaie

5, Place de la Monnaie