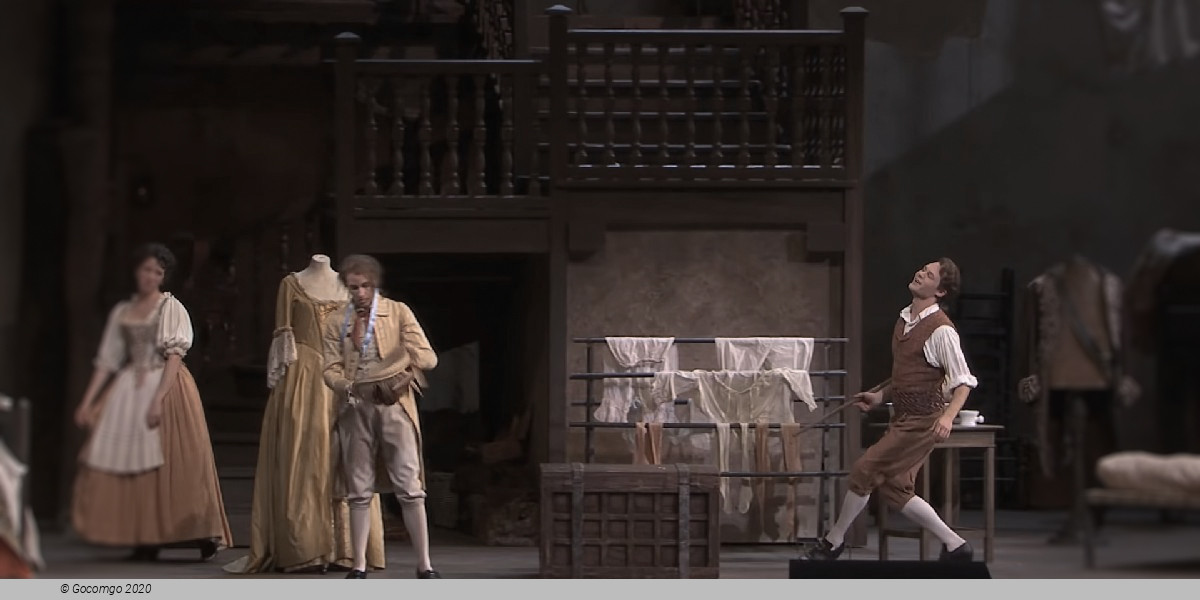

Act I

Merry wedding preparations are underway at the home of Count Almaviva. Count Almaviva’s valet is marrying Susanna, the Countess’ maidservant. The impending festivities bring the Count no joy whatsoever: he has taken a fancy to the bride-to-be himself and is looking for some reason to prevent the marriage. Susanna anxiously tells her future husband of the Count’s amorous intentions. Figaro is ready to employ all his cunning and inventiveness to ruin his master’s machinations. The convivial Figaro, however, has many enemies. To this day, old Bartolo has been unable to forget his former barber’s cunning, aiding the Count to marry his ward Rosina. The ageing housekeeper Marcellina dreams of marrying Figaro herself. Both Bartolo and she hope that the Count, frustrated by Susanna’s uncompromising nature, will help them. Marcellina greets Susanna with ceremonious curtsies and spiteful compliments. Susanna merrily and wittily laughs at the shrewish old woman. Cherubino appears. The young page is in love with every woman in the castle. He idolises the Countess, but is not averse to making advances to Susanna to whom he has come to share his woes – the Count found him with Barbarina, the gardener’s daughter, and has driven him from the castle.

The Count arrives unexpectedly, forcing Cherubino to hide.

The Count again begs Susanna to accept his overtures, but the amorous grandee’s declarations are interrupted by a knock at the door – it is the scheming Basilio. The Count’s jealousy has been roused by the old gossip’s hints at Cherubino’s love for the Countess. Enraged, he tells Susanna and Bartolo of the page’s tricks and then suddenly spots Cherubino in his hiding place. The Count’s fury knows no bounds. Cherubino is immediately ordered to enlist in the army. Figaro consoles him.

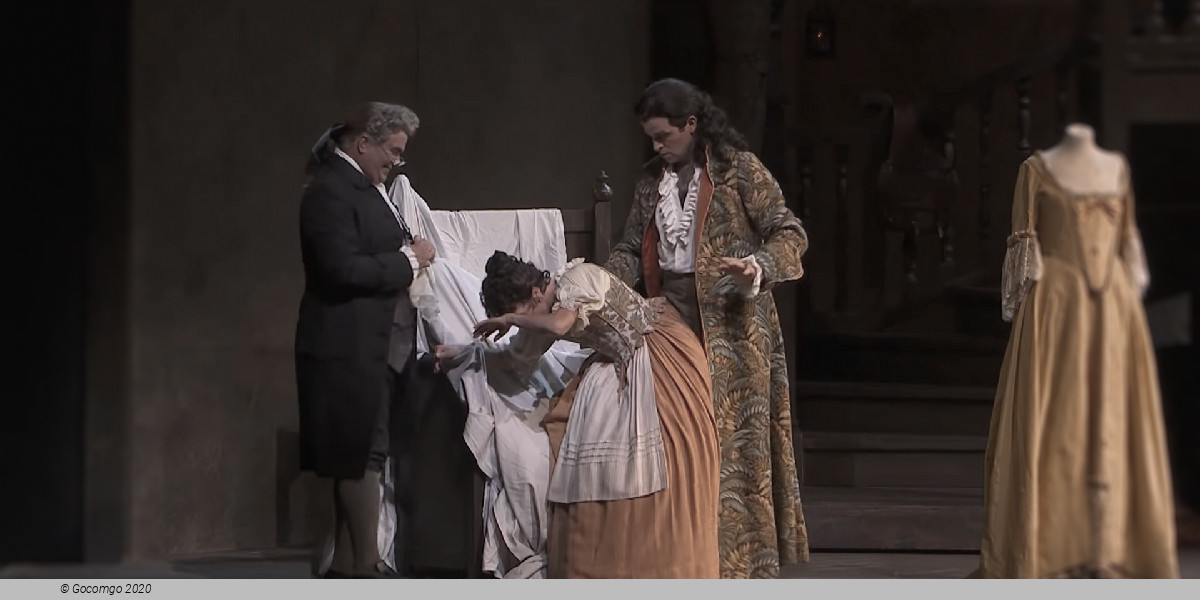

Act II

The Countess is distressed at her husband’s indifference. Susanna’s tale of his infidelity wounds her to the quick. Sincerely empathetic towards her maidservant and her groom, the Countess eagerly adopts Figaro’s plan to call the Count into the garden at night and send Cherubino in a woman’s dress to meet him instead of Susanna. Susanna immediately begins to disguise the page. The Count’s sudden appearance throws all into confusion. They hide Cherubino in the room next door.

Surprised at his wife’s confusion, the Count demands she unlock the door. The Countess adamantly refuses, saying that only Susanna is there. The Count’s jealous suspicions become stronger. Resolving to break down the door, the Count departs with his wife to fetch some tools. The quick-witted Susanna helps Cherubino out of his hiding place – but where should he run? All the doors are locked. In panic, the poor page has to jump out of the window.

Returning, the Count finds Susanna behind the locked door, laughing at his suspicions. He is forced to as k forgiveness from his wife. Figaro runs in and announces that the guests have already arrived. The Count, however, delays the start of the festivities – he will wait for Marcellina to arrive. The housekeeper appears, demanding that Figaro either repay her an old debt or marry her. Figaro and Susanna’s wedding is postponed.

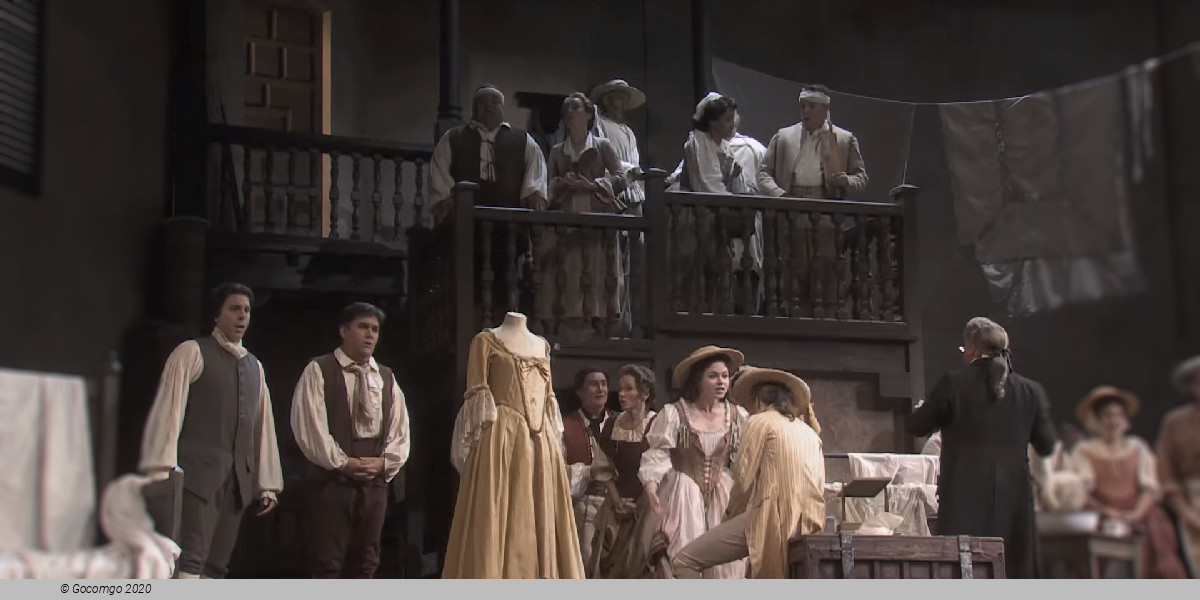

Act III

The court has decided in favour of Marcellina. The Count is victorious, though his triumph is short-lived. It suddenly transpires that Figaro is Marcellina and Bartolo’s own son, kidnapped by bandits as a child. Figaro’s deeply affected parents resolve to marry. Now two weddings are to be celebrated.

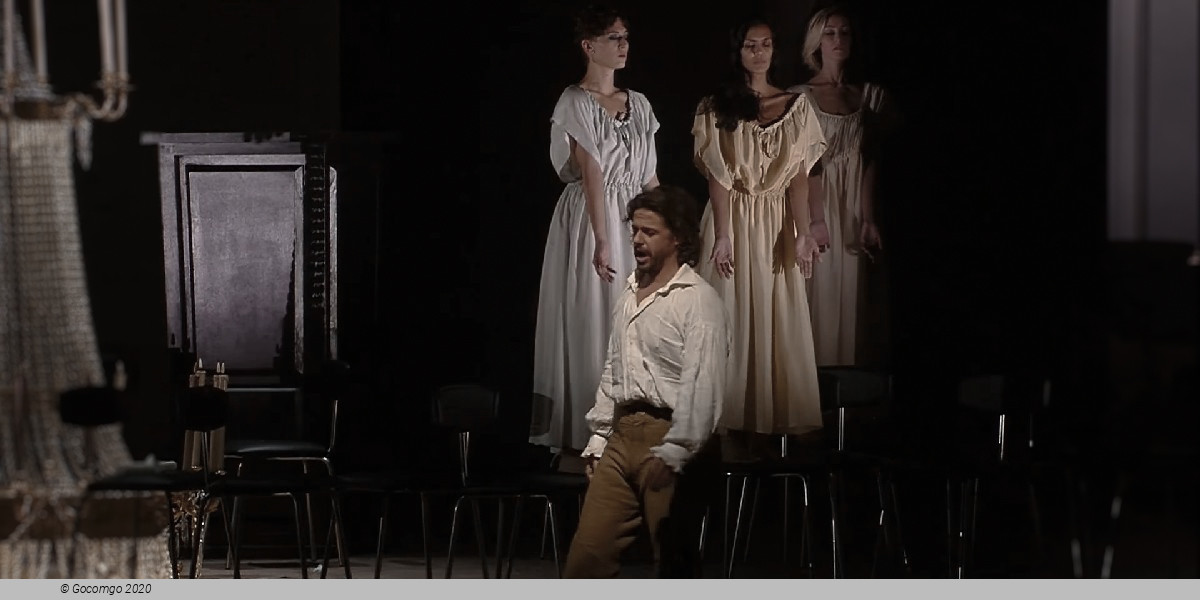

Act IV

The Countess and Susanna cannot drop the idea of teaching the Count a lesson. The Countess decides to wear her maidservant’s dress herself and go to the midnight rendezvous. Under her dictation, Susanna writes a note appointing a meeting with the Count in the garden. Barbarina is to pass the message during the festivities. Figaro laughs at his master but, learning from the unaffected Barbarina that the note was written by Susanna, he begins to suspect his wife of adultery. In the darkness of the garden at midnight, he recognises the disguised Susanna, but makes as if he knows her to be the Countess. The Count does not recognise his wife dressed as the maidservant and draws her into the gazebo. Seeing Figaro declaring love to the false Countess, he raises a scandal and calls on witnesses so he can publicly accuse his wife of infidelity. He refuses all prayers for forgiveness. But here the real Countess appears and removes her mask. The Count is in disgrace and begs his wife’s forgiveness.

The play is set at the castle of Aguas Frescas, three leagues from Seville.

Act I

The play begins in a room in the Count's castle—the bedroom to be shared by Figaro and Suzanne after their wedding, which is set to occur later that day. Suzanne reveals to Figaro her suspicion that the Count gave them this particular room because it is so close to his own, and that the Count has been pressing her to begin an affair with him. Figaro at once goes to work trying to find a solution to this problem. Then Dr. Bartholo and Marceline pass through, discussing a lawsuit they are to file against Figaro, who owes Marceline a good deal of money and has promised to marry her if he fails to repay the sum; his marriage to Suzanne will potentially void the contract. Bartholo relishes the news that Rosine is unhappy in her marriage, and they discuss the expectation that the Count will take Figaro's side in the lawsuit if Suzanne should submit to his advances. Marceline herself is in love with Figaro, and hopes to discourage Suzanne from this.

After a brief confrontation between Marceline and Suzanne, a young pageboy named Chérubin comes to tell Suzanne that he has been dismissed for being caught hiding in the bedroom of Fanchette. The conversation is interrupted by the entrance of the Count, and since Suzanne and Chérubin do not want to be caught alone in a bedroom together, Chérubin hides behind an armchair. When the Count enters, he propositions Suzanne (who continues to refuse to sleep with him). They are then interrupted by Bazile's entrance. Again, not wanting to be found in a bedroom with Suzanne, the Count hides behind the armchair. Chérubin is forced to throw himself on top of the armchair so the Count will not find him, and Suzanne covers him with a dress so Bazile cannot see him. Bazile stands in the doorway and begins to tell Suzanne all the latest gossip. When he mentions a rumour that there is a relationship between the Countess and Chérubin, the Count becomes outraged and stands up, revealing himself. The Count justifies his firing Chérubin to Bazile and the horrified Suzanne (now worried that Bazile will believe that she and the Count are having an affair). The Count re-enacts finding Chérubin behind the door in Fanchette's room by lifting the dress covering Chérubin, accidentally uncovering Chérubin's hiding spot for the second time. The Count is afraid that Chérubin will reveal the earlier conversation in which he was propositioning Suzanne, and so decides to send him away at once as a soldier. Figaro then enters with the Countess, who is still oblivious to her husband's plans. A troupe of wedding guests enters with him, intending to begin the wedding ceremony immediately. The Count is able to persuade them to hold it back a few more hours, giving himself more time to enact his plans.

Act II

The scene is the Countess's bedroom. Suzanne has just broken the news of the Count's action to the Countess, who is distraught. Figaro enters and tells them that he has set in motion a new plan to distract the Count from his intentions toward Suzanne by starting a false rumour that the Countess is having an affair and that her lover will appear at the wedding; this, he hopes, will motivate the Count to let the wedding go ahead. Suzanne and the Countess have doubts about the effectiveness of the plot; they decide to tell the Count that Suzanne has agreed to his proposal, and then to embarrass him by sending out Chérubin dressed in Suzanne's gown to meet him. They stop Chérubin from leaving and begin to dress him, but just when Suzanne steps out of the room, the Count comes in. Chérubin hides, half dressed, in the adjoining dressing room while the Count grows increasingly suspicious, especially after having just heard Figaro's rumour of the Countess's affair. He leaves to get tools to break open the dressing room door, giving Chérubin enough time to escape through the window and Suzanne time to take his place in the dressing room; when the Count opens the door, it appears that Suzanne was inside there all along. Just when it seems he calms down, the gardener Antonio runs in screaming that a half-dressed man just jumped from the Countess's window. The Count's fears are settled again once Figaro takes credit to being the jumper, claiming that he started the rumour of the Countess having an affair as a prank and that while he was waiting for Suzanne he became frightened of the Count's wrath, jumping out the window in terror. Just then Marceline, Bartholo and the judge Brid'oison come to inform Figaro that his trial is starting.

Act III

Figaro and the Count exchange a few words, until Suzanne, at the insistence of the Countess, goes to the Count and tells him that she has decided that she will begin an affair with him, and asks he meet her after the wedding. The Countess has actually promised to appear at the assignation in Suzanne's place. The Count is glad to hear that Suzanne has seemingly decided to go along with his advances, but his mood sours again once he hears her talking to Figaro and saying it was only done so they might win the case.

Court is then held, and after a few minor cases, Figaro's trial occurs. Much is made of the fact that Figaro has no middle or last name, and he explains that it is because he was kidnapped as a baby and doesn't know his real name. The Count rules in Marceline's favour, effectively forcing Figaro to marry her, when Marceline suddenly recognizes a birthmark (or scar or tattoo; the text is unclear) in the shape of a spatule (lobster) on Figaro's arm—he is her son, and Dr. Bartholo is his father. Just then Suzanne runs in with enough money to repay Marceline, given to her by the Countess. At this, the Count storms off in outrage.

Figaro is thrilled to have rediscovered his parents, but Suzanne's uncle, Antonio, insists that Suzanne cannot marry Figaro now, because he is illegitimate. Marceline and Bartholo are persuaded to marry in order to correct this problem.

Act IV

Figaro and Suzanne talk before the wedding, and Figaro tells Suzanne that if the Count still thinks she is going to meet him in the garden later, she should just let him stand there waiting all night. Suzanne promises, but the Countess grows upset when she hears this news, thinking that Suzanne is in the Count's pocket and is wishing she had kept their rendezvous a secret. As she leaves, Suzanne falls to her knees, and agrees to go through with the plan to trick the Count. Together they write a note to him entitled "A New Song on the Breeze" (a reference to the Countess's old habit of communicating with the Count through sheet music dropped from her window), which tells him that she will meet him under the chestnut trees. The Countess lends Suzanne a pin from her dress to seal the letter, but as she does so, the ribbon from Chérubin falls out of the top of her dress. At that moment, Fanchette enters with Chérubin disguised as a girl, a shepherdess, and girls from the town to give the Countess flowers. As thanks, the Countess kisses Chérubin on the forehead. Antonio and the Count enter—Antonio knows Chérubin is disguised because they dressed him at his daughter's (Fanchette's) house. The Countess admits to hiding Chérubin in her room earlier and the Count is about to punish him. Fanchette suddenly admits that she and the Count have been having an affair, and that, since he has promised he will give her anything she desires, he must not punish Chérubin but give him to her as a husband. Later, the wedding is interrupted by Bazile, who had wished to marry Marceline himself; but once he learns that Figaro is her son he is so horrified that he abandons his plans. Later, Figaro witnesses the Count opening the letter from Suzanne, but thinks nothing of it. After the ceremony, he notices Fanchette looking upset, and discovers that the cause is her having lost the pin that was used to seal the letter, which the Count had told her to give back to Suzanne. Figaro nearly faints at the news, believing Suzanne's secret communication means that she has been unfaithful and, restraining tears, he announces to Marceline that he is going to seek vengeance on both the Count and Suzanne.

Act V

In the castle gardens beneath a grove of chestnut trees, Figaro has called together a group of men and instructs them to call together everyone they can find: he intends to have them all walk in on the Count and Suzanne in flagrante delicto, humiliating the pair and also ensuring ease of obtaining a divorce. After a tirade against the aristocracy and the unhappy state of his life, Figaro hides nearby. The Countess and Suzanne then enter, each dressed in the other's clothes. They are aware that Figaro is watching, and Suzanne is upset that her husband would doubt her so much as to think she would ever really be unfaithful to him. Soon afterward the Count comes, and the disguised Countess goes off with him. Figaro is outraged, and goes to the woman he thinks is the Countess to complain; he realises that he is talking to his own wife Suzanne, who scolds him for his lack of confidence in her. Figaro agrees that he was being stupid, and they are quickly reconciled. Just then the Count comes out and sees what he thinks is his own wife kissing Figaro, and races to stop the scene. At this point, all the people who had been instructed to come on Figaro's orders arrive, and the real Countess reveals herself. The Count falls to his knees and begs her for forgiveness, which she grants. After all other loose ends are tied up, the cast breaks into song before the curtain falls.

Figaro's speech

One of the defining moments of the play—and Louis XVI's particular objection to the piece—is Figaro's long monologue in the fifth act, directly challenging the Count:

No, my lord Count, you shan't have her... you shall not have her! Just because you are a great nobleman, you think you are a great genius—Nobility, fortune, rank, position! How proud they make a man feel! What have you done to deserve such advantages? Put yourself to the trouble of being born—nothing more. For the rest—a very ordinary man! Whereas I, lost among the obscure crowd, have had to deploy more knowledge, more calculation and skill merely to survive than has sufficed to rule all the provinces of Spain for a century!

[...]

I throw myself full-force into the theatre. Alas, I might as well have put a stone round my neck! I fudge up a play about the manners of the Seraglio; a Spanish author, I imagined, could attack Mahomet without scruple; but immediately some envoy from goodness-knows-where complains that some of my lines offend the Sublime Porte, Persia, some part or other of the East Indies, the whole of Egypt, the kingdoms of Cyrenaica, Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers and Morocco. Behold my comedy scuppered to please a set of Mohammedan princes—not one of whom I believe can read—who habitually beat a tattoo on our shoulders to the tune of "Down with the Christian dogs!" Unable to break my spirit, they decided to take it out on my body. My cheeks grew hollowed: my time was out. I saw in the distance the approach of the fell sergeant, his quill stuck into his wig.

[...]

I'd tell him that stupidities acquire importance only in so far as their circulation is restricted, that unless there is liberty to criticize, praise has no value, and that only trivial minds are apprehensive of trivial scribbling

1 Theatre Square

1 Theatre Square