Place: A convent in Italy

Time: The latter part of the 17th century

The opera opens with scenes showing typical aspects of life in the convent – all the sisters sing hymns, the Monitor scolds two lay-sisters, everyone gathers for recreation in the courtyard. The sisters rejoice because, as the mistress of novices explains, this is the first of three evenings that occur each year when the setting sun strikes the fountain so as to turn its water golden. This event causes the sisters to remember Bianca Rosa, a sister who has died. Sister Genevieve suggests they pour some of the "golden" water onto her tomb.

The nuns discuss their desires. While the Monitor believes that any desire at all is wrong, Sister Genevieve confesses that she wishes to see lambs again because she used to be a shepherdess when she was a girl, and Sister Dolcina wishes for something good to eat. Sister Angelica claims to have no desires, but as soon as she says so, the nuns begin gossiping – Sister Angelica has lied, because her true desire is to hear from her wealthy, noble family, whom she has not heard from in seven years. Rumors are that she was sent to the convent in punishment.

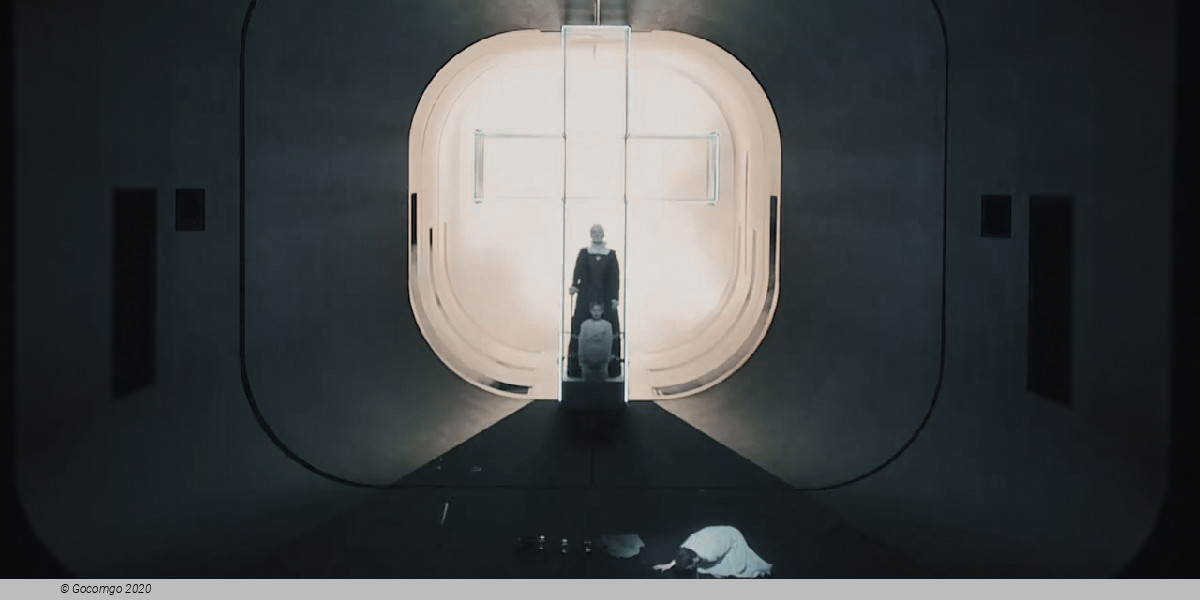

The conversation is interrupted by the Infirmary Sister, who begs Sister Angelica to make a herbal remedy, her specialty. Two tourières arrive, bringing supplies to the convent, and news that a grand coach is waiting outside. Sister Angelica becomes nervous and upset, thinking rightly that someone in her family has come to visit her. The Abbess chastises Sister Angelica for her inappropriate excitement and announces the visitor, the Princess, Sister Angelica's aunt.

The Princess explains that Angelica's sister is to be married and that Angelica must sign a document renouncing her claim to her inheritance. Angelica replies that she has repented for her sin, but she cannot offer up everything in sacrifice to the Virgin – she cannot forget the memory of her illegitimate son, who was taken from her seven years ago. The Princess at first refuses to speak, but finally informs Sister Angelica that her son died of fever two years ago. Sister Angelica, devastated, signs the document and collapses in tears. The Princess leaves.

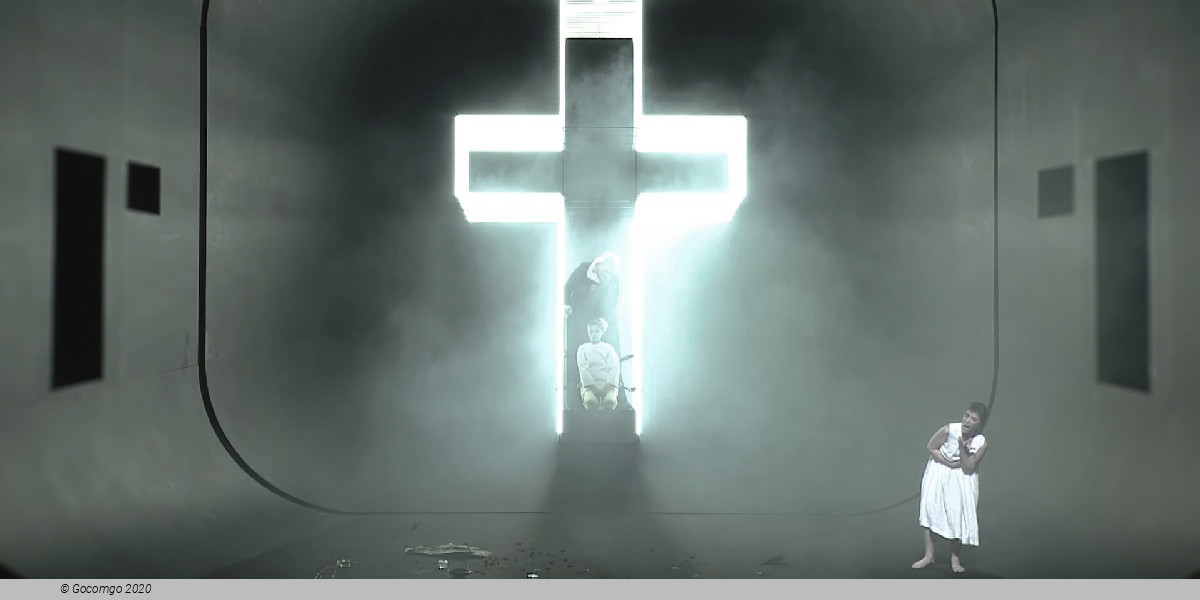

Sister Angelica is seized by a heavenly vision – she believes she hears her son calling for her to meet him in paradise. She makes a poison and drinks it, but realizes that in committing suicide, she has committed a mortal sin and has damned herself to eternal separation from her son. She begs the Virgin Mary for mercy and, as she dies, she sees a miracle: the Virgin Mary appears, along with Sister Angelica's son, who runs to embrace her.

Setting Florence, 1299

The rich old Buoso Donati has died. His family express their grief to one another. However, in reality they are all thinking of the deceased’s will. There are rumours that he has left everything to a monastery in San Reparata. Surely this can’t be true? The relatives turn for advice to the seventy-year-old Simone, the cousin of the dead man, who was once mayor of Fuccecio. Simone says that if the will is in the house something may yet be done. Everyone starts to search for the document that will reveal the dead man’s wishes. It is found by Rinuccio, the young nephew of Zita, Buoso’s cousin. Unlike the deceased’s other relatives, he thinks little of money. His thoughts are taken up with Lauretta, Gianni Schicchi’s daughter. They love one another. But the elderly aunt is indifferent to the match. Zita promises her blessing on one condition – if the testament fills their pockets and there is no longer any need to think of the potential income from a dowry. Full of hope at the deliverance the will might lend, Rinuccio sends the young Gherardino for Schicchi and his daughter. The reading of Buoso Donati’s last will confirms the worst – all is to go to the monks. The relatives react with rage. Rinuccio suggests getting advice from Gianni Schicchi. Buoso’s relatives want nothing to do with him, considering him a vulgar peasant who is below them. Rinuccio defends the father of his beloved, praising the ingenuity of those who have, like him, come from outside Florence to make it a greater place. Gianni Schicchi appears with his daughter Lauretta. He is insulted almost from the outset, and the marriage refused on the grounds that Lauretta has no dowry to offer. Initially refusing to help, his daughter’s plea convinces him to intervene. Sending his daughter onto the balcony, Schicchi orders the body be taken into another room, the bed to be made and that all traces of mourning be removed. Suddenly there is a knock at the door – Dr Spinelloccio has come to see his patient. Hidden, Schicchi imitates Buoso Donati’s voice, telling the doctor he is much better and asking him to return later. The doctor leaves singing the praises of Bolognese medicine.

Gianni Schicchi reveals his plan. All are convinced that he can copy the dead man’s voice to perfection. And if he can imitate his appearance too then he can dictate a new will to the notary. The relatives are delighted and begin to discuss the division of the property. Outside the window a funeral bell sounds and excitement turns to terror – surely Buoso’s death has not been discovered? But it is a false alarm. One after the other, Donati’s relatives, unknown to each other, try to bribe Gianni Schicchi to give them the most valuable share of the inheritance. Schicchi promises to do as each asks, but reminds them that forgery is punishable by law and the penalty the cutting off of a hand. The relatives are worried. But even fear of a frightful punishment cannot stop them dreaming of riches. Having changed his clothes, Schicchi gets into Buoso’s death bed.

Accompanied by two witnesses – Guccio and Pinellino – Ser Amantio di Nicolao the local notary appears. The “dying man” informs him that his paralysed arm has left him unable to write, so his will must be dictated. He asks for “his family” to be present when the document is prepared. Then, after initially sharing the wealth as agreed, the false Buoso wills his most valuable property to his “great friend Gianni Schicchi”. The relatives are beside themselves in fury but are powerless. If they expose this crafty villain they will put their own necks in the noose. When the notary departs, all the cousins and their spouses fall upon Schicchi. But as the new master he orders them all out. Rinuccio and Lauretta are able to love in peace and sing of their future together. The old Zita cannot prevent their marriage. Gianni Schicchi turns to the audience and asks them to forgive him his little deceit because of the mitigating circumstances. Despite being banished to hell, he argues that all could not have turned out better. He says that the great Dante also forgives him and expresses his gratitude for providing the subject of the work.

Place: Florence

Time: 1299

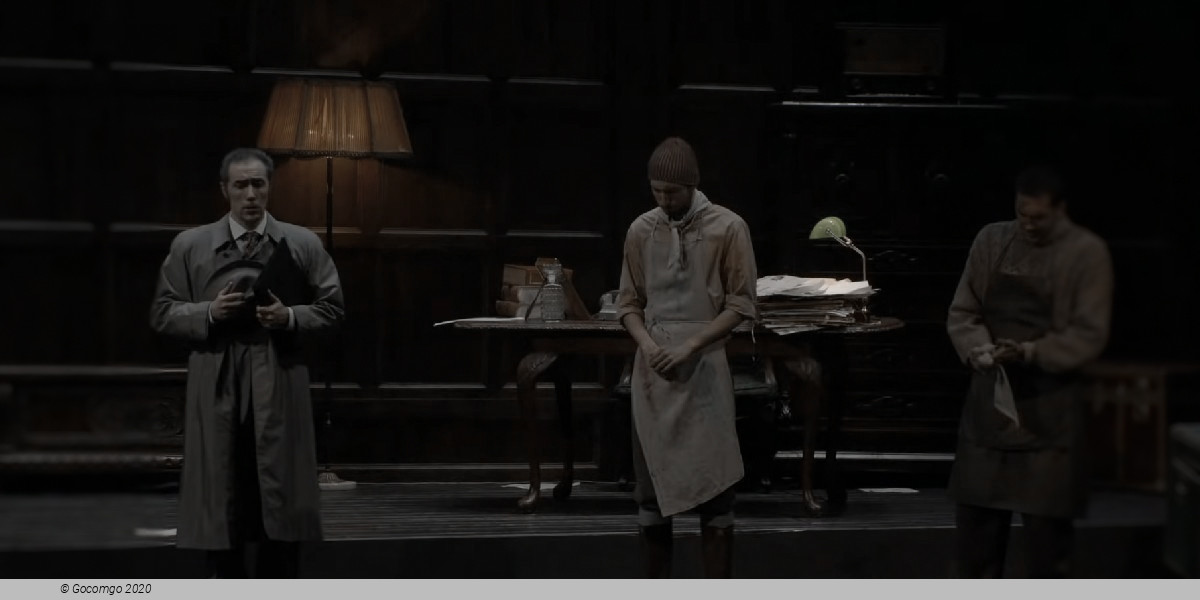

As Buoso Donati lies dead in his curtained four-poster bed, his relatives gather round to mourn his passing, but are really more interested in learning the contents of his will. Among those present are his cousins Zita and Simone, his poor-relation brother-in-law Betto, and Zita's nephew Rinuccio. Betto mentions a rumour he has heard that Buoso has left everything to a monastery; this disturbs the others and precipitates a frantic search for the will. The document is found by Rinuccio, who is confident that his uncle has left him plenty of money. He withholds the will momentarily and asks Zita to allow him to marry Lauretta, daughter of Gianni Schicchi, a newcomer to Florence. Zita replies that if Buoso has left them rich, he can marry whom he pleases; she and the other relatives are anxious to begin reading the will. A happy Rinuccio sends little Gherardino to fetch Schicchi and Lauretta.

As they read, the relatives' worst fears are soon realised; Buoso has indeed bequeathed his fortune to the monastery. They break out in woe and indignation and turn to Simone, the oldest present and a former mayor of Fucecchio, but he can offer no help. Rinuccio suggests that only Gianni Schicchi can advise them what to do, but this is scorned by Zita and the rest, who sneer at Schicchi's humble origins and now say that marriage to the daughter of such a peasant is out of the question. Rinuccio defends Schicchi in an aria "Avete torto" (You're mistaken), after which Schicchi and Lauretta arrive. Schicchi quickly grasps the situation, and Rinuccio begs him for help, but Schicchi is rudely told by Zita to "be off" and take his daughter with him. Rinuccio and Lauretta listen in despair as Schicchi announces that he will have nothing to do with such people. Lauretta makes a final plea to him with "O mio babbino caro" (Oh, my dear papa), and he agrees to look at the will. After twice scrutinizing it and concluding that nothing can be done, an idea occurs to him. He sends his daughter outside so that she will be innocent of what is to follow.

First, Schicchi establishes that no one other than those present knows that Buoso is dead. He then orders the body removed to another room. A knock announces the arrival of the doctor, Spinelloccio. Schicchi conceals himself behind the bed curtains, mimics Buoso's voice and declares that he's feeling better; he asks the doctor to return that evening. Boasting that he has never lost a patient, Spinelloccio departs. Schicchi then unveils his plan in the aria "Si corre dal notaio" (Run to the notary); having established in the doctor's mind that Buoso is still alive, Schicchi will disguise himself as Buoso and dictate a new will. All are delighted with the scheme, and importune Schicchi with personal requests for Buoso's various possessions, the most treasured of which are "the mule, the house and the mills at Signa". A funeral bell rings, and everyone fears that the news of Buoso's death has emerged, but it turns out that the bell is tolling for the death of a neighbour's Moorish servant. The relatives agree to leave the disposition of the mule, the house and the mills to Schicchi, though each in turn offers him a bribe. The women help him to change into Buoso's clothes as they sing the lyrical trio "Spogliati, bambolino" (Undress, little boy). Before taking his place in the bed, Schicchi warns the company of the grave punishment for those found to have falsified a will: exile from Florence together with the loss of a hand.

The notary arrives, and Schicchi starts to dictate the new will, declaring any prior will null and void. To general satisfaction he allocates the minor bequests, but when it comes to the mule, the house and the mills, he orders that these be left to "my devoted friend Gianni Schicchi". Incredulous, the family can do nothing while the lawyer is present, especially when Schicchi slyly reminds them of the penalties that discovery of the ruse will bring. Their outrage when the notary leaves is accompanied by a frenzy of looting as Schicchi chases them out of what is now his house.

Meanwhile, Lauretta and Rinuccio are rapt in a love duet, "Lauretta mia" - there is no bar to their marriage since Schicchi can provide a respectable dowry. Schicchi, returning, stands moved at the sight of the two lovers. He turns to the audience and asks them to agree that no better use could be found for Buoso's wealth: although the poet Dante has condemned him to hell for this trick, Schicchi asks the audience to forgive him in light of "extenuating circumstances."

1 Theatre Square

1 Theatre Square