A feast for Balanchine devotees.

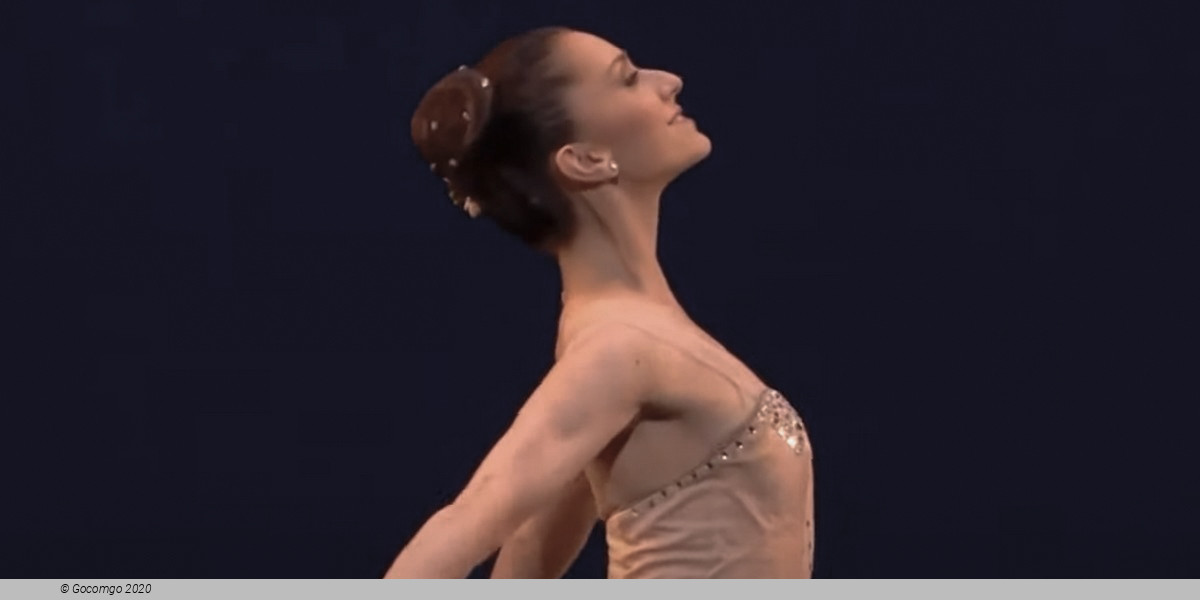

The oldest Balanchine ballet in the repertory, the neoclassical masterwork Apollo, first staged in 1928, leads a bill that traces the choreographer’s work across an astonishing half-century. Also on the program is the exhilarating Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux, a supremely stylish dance created to music originally written for Swan Lake. And representing the latter years of Balanchine’s career are two dances created in the 1970s: the vivacious Ballo della Regina, with its quicksilver choreography and sprightly music by Giuseppe Verdi, and the entrancing Chaconne, which includes a memorably beautiful pas de deux and a thrilling ensemble finale, set to music drawn from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice.

Balanchine's first collaboration with Stravinsky and one of his earliest international successes, Apollo presents the young god as he is ushered into adulthood by the muses of poetry, mime, and dance.

"Apollo I look back on as the turning point of my life. In its discipline and restraint, in its sustained oneness of tone and feeling, the score was a revelation. It seemed to tell me that I could dare not to use everything, that I, too, could eliminate."

George Balanchine

Apollo is the oldest Balanchine ballet in New York City Ballet’s repertory. Created for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and originally titled Apollon Musagète, the ballet premiered in Paris in 1928 and was Balanchine’s first major collaboration with composer Igor Stravinsky. With this dramatic and powerful ballet, which created a sensation when it was first performed, the 24-year-old Balanchine achieved international recognition. The 1928 premiere of the ballet featured sets and costumes by the French painter André Bauchant and in 1929 new costumes were created by Coco Chanel. The ballet was first performed by New York City Ballet in 1951, and during his lifetime Balanchine continued to revise the work, eliminating sets, costumes, and much of the ballet’s narrative content.y Ballet revival, actor Jack Noseworthy served as the narrator.

Scenery and costumes for Balanchine's production were by French artist André Bauchant. Coco Chanel provided new costumes in 1929. Apollo wore a reworked toga with a diagonal cut, a belt, and laced up. The Muses wore a traditional tutus. The decoration was baroque: two large sets, with some rocks and Apollo's chariot. In the dance a certain academicism resurfaced in the stretching out and upward leaping of the body, but the Balanchine bent the angles of the arms and hands to define instead the genre of neoclassical ballet.

The jaw-dropping technical feats of Ballo della Regina’s choreography were originally devised to challenge the lead ballerina, who must exhibit carefree joyousness while performing steps that push the limits of physical possibility.

Balanchine was no stranger to opera. Not only did he create ballets to the music from such works as La Sonnambula and Don Sebastian, he also choreographed the ballet portions of many opera productions. He felt that opera taught something important. "From Verdi's way of dealing with the chorus," Balanchine told biographer Bernard Taper, "I have learned how to handle the corps de ballet, the ensemble, the soloists, how to make the soloists stand out against the corps, and when to give them a rest."

Ballo della Regina is a virtuoso set of variations, comparable to the bel canto style of opera. It is set to ballet music that was cut from the original production of Verdi's Don Carlo. Lincoln Kirstein writes that the ballet seems to take place in a grotto, with reference through lighting and costumes to the original tale of a fisherman's search for the perfect pearl.

The ballet is one of George Balanchine’s last works, and the choreography requires ballerinas to push the limits of their physical abilities while radiating carefree cheerfulness.

A virtuosic ballet, Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux is brief, beautiful, and beloved – an adrenaline rush for both dancers and audiences.

For the original production of Swan Lake in Moscow in 1877, Tschaikovsky composed a pas de deux for Act III at the request of Anna Sobeshchanskaya, a Bolshoi prima ballerina who was one of the first dancers to perform the lead role. Since it was composed later than the rest of the music, it was not included in the published score and was therefore not available to Marius Petipa when he choreographed his famous Swan Lake in St. Petersburg, in 1895. In its place, Petipa moved some music from Act I to Act III, and it is this piece that is now well-known as the Black Swan pas de deux. Well over half a century later, the complete and original Swan Lake score was found, including an appendix with the lost pas de deux. Hearing of its historic discovery, George Balanchine asked for — and was granted — permission to use it for his own choreography. The result is an eight-minute display of ballet bravura and technique.

By turns elegiac and courtly, Chaconne begins with a dreamlike prologue and concludes with a grand series of classical dances.

A chaconne is a dance, built on a short phrase in the bass, that was often used by composers of the 17th and 18th centuries to end an opera in a festive mood. This choreography, first performed in the 1963 Hamburg State Opera production of Orfeo ed Euridice, was somewhat altered for presentation as the ballet Chaconne particularly in the sections for the principal dancers.

Balanchine's first Orfeo was made for the Metropolitan Opera in 1936. His novel approach — the singers remained in the pit while the action was danced on stage — was not well received, and the production had only two performances. In addition to the Hamburg production, he choreographed other versions of the opera for the Théâtre National de l'Opéra, Paris in 1973 and the Chicago Lyric Opera in 1975.

While having roots in earlier opera productions, Chaconne is pure dance. The opening pas de deux and following ensemble are lyrical and flowing. The second part has the spirit of a court entertainment, with formal divertissements, bravura roles for the principal dancers, and, of course, a concluding chaconne.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza