The premiere of The Bright Stream took place in Leningrad Minor Opera and Ballet Theatre on April 4, 1935. Both audience and critics accepted the ballet eagerly so it was decided to be staged on the country’s main stage.

On November 30, same year, The Bright Stream was presented at the Bolshoi, adding to the leading soloists’ repertoire. The cast for the main parts included Asaf and Sulamith Messerer, Sofia Golovkina, Aleksei Yermolaev, Zinaida Vasilieva and Pyotr Gusev – one of the future artistic directors of the Bolshoi Ballet… Audience enjoyed the merry performance, and its choreographer Fyodor Lopukhov looked forward to become the artistic director of the Bolshoi ballet company. All the more unexpected was the denouement which destroyed The Bright Stream. Stalin had forbidden it. A smasher appeared in the country’s main communist party newspaper Pravda on February 6, 1936. They thought the comedy with traditional nice balletic extravagance to be a parody on happy Soviet life like it was customary to picture it then.

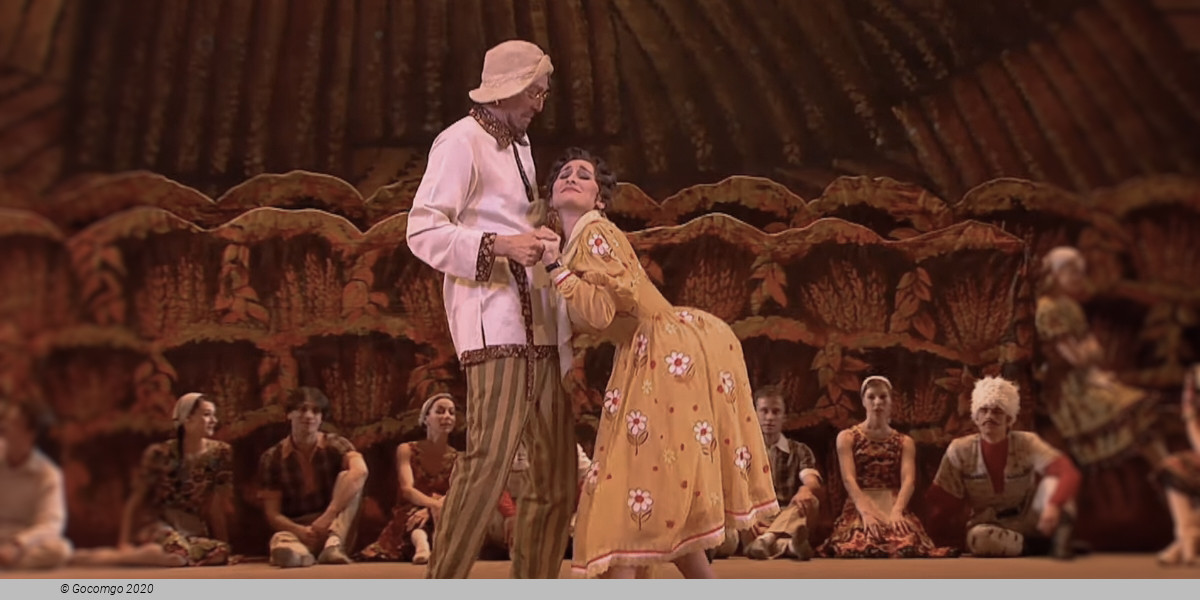

The idea to revive the ballet by Shostakovich belongs to Alexei Ratmansky. He was enchanted by the music and, as he himself confessed, saw and heard all libretto twists and turns in it. The premiere took place on April 18, 2003. For Ratmansky, the main quality of The Stream music was its balletability as if it was Minkus yet a genius one. They used to stage full-scale classical ballets to music by Minkus. And Ratmansky complied the cannon, even paying tribute to traditional balletic pantomime. It may be postmodernism yet a light-breathing or rather light-pacing one.

The one to dive gladly into kitch-parody element was the set designer Boris Messerer, whose father and aunt danced, of course, in quite different setting back in 1930s. “Restored” slogans and posters of the Soviet era are pointedly smiling to taglines and bumpers of our time.

DANCE of DEATH

With its dancing farmers and cycling dog, Shostakovich thought his ballet The Bright Stream would delight Stalin. Instead, one of its creators was sent to the gulag. Now the Bolshoi has finally resurrected it.

In the mass of Shostakovich centenary events that have taken place this year, ballet fans haven’t had much to celebrate. It’s not that the composer ignored the form — between 1929 and 1935, he wrote a trio of full-length ballet scores: The Golden Age, The Bolt and The Bright Stream. All three, though, were banned shortly after their premieres, leaving Shostakovich’s reputation so damaged, he was reluctant ever to write for the lyric stage again.

It’s a cause of great regret for Russia’s monolithic ballet companies, the Kirov and the Bolshoi. Both are aware that, had Shostakovich been given full artistic freedom, he may have become one of the great modern ballet composers — as inspirational for the dance-makers of Soviet Russia as Stravinsky was for choreographers in the west. Instead, the two companies must content themselves with acts of restitution. This summer, as part of its 10-day Shostakovich festival at the Coliseum in London, the Kirov is performing The Golden Age, while over at the Royal Opera House, the Bolshoi is presenting the first British performances of The Bright Stream.

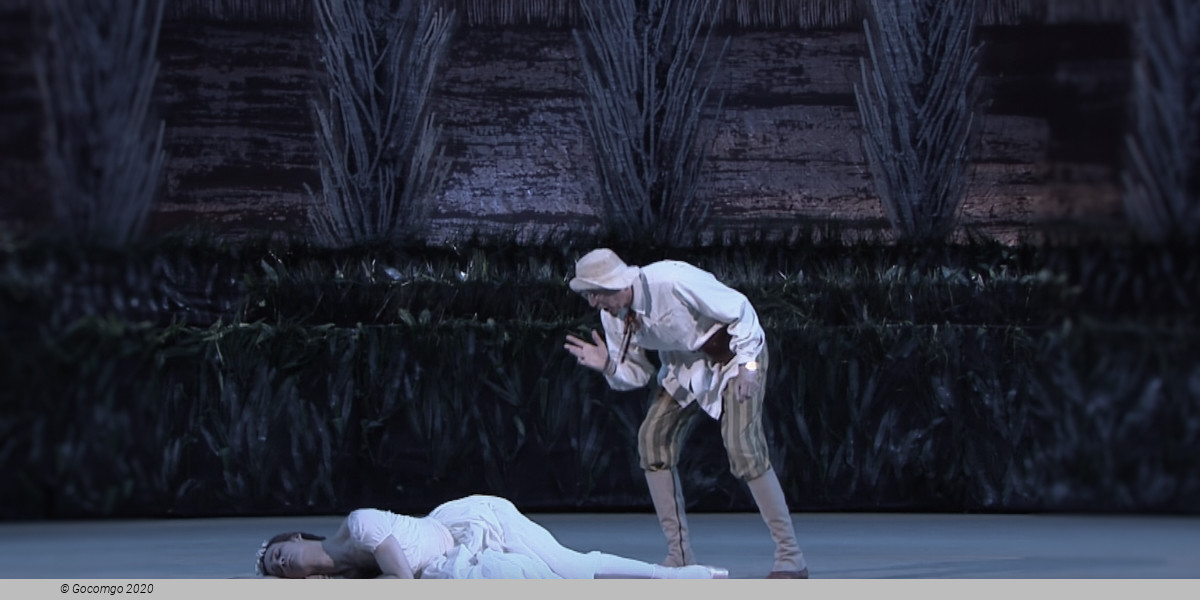

Of the three ballets, it was The Bright Stream that was punished most grotesquely. The ballet’s co-librettist, Adrian Piotrovsky, was sent to a gulag and never heard of again, while the creative career of its choreographer, Fedor Lopukhov, was all but terminated. Shostakovich’s music was never again played during the Soviet era, beyond a heavily edited suite of his most popular tunes.

Alexei Ratmansky, now director of the Bolshoi, first came across the full score in a recording made by Rozhdestvensky in Stockholm in 1995. He was determined to get it back on to the Russian stage. “It sounded incredible. I couldn’t believe that no one had returned to it before. The music is just so danceable, with this wonderful variety of adagios, waltzes and polkas. It’s like Minkus but all on the level of Shostakovich’s genius.”

At the time, Ratmansky knew Lopukhov’s name only from books. But as he researched the history of The Bright Stream, he realised that it was more than a fine piece of dance music that had been abandoned. It was a remarkable ballet, choreographed by one of the most sophisticated, subversive talents of the Soviet period.

Born in 1886, Lopukhov was among the last generation to be raised in the tsar’s Imperial Ballet — and among the first generation to test its wings in the 20th century. He was a protege of the radical choreographer Mikhail Fokine, and he briefly travelled abroad, spending 1910-11 touring in American vaudeville with his sister. When ballet was up for grabs in the wake of the 1917 revolution, Lopukhov was ideally placed to lead it. As director of the Kirov (then known as Gatob) in the 1920s, he created a repertory that may never have been equalled for its balance between traditional classics and avant-garde experiment.

As Russian culture began to ossify under Stalin’s rule, however, life became difficult for versatile, inquisitive artists like Lopukhov. Ballet itself was still in official favour — Stalin was often to be seen slipping into a performance of Swan Lake. But to choreograph new repertory became risky.

On the face of it, The Bright Stream should have been a riotous success with Stalin’s regime — it was set on a collective farm. But Lopukhov had also worked out a clever comic libretto of romantic flirtations and theatrical encounters that allowed his choreography to range from virtuoso classical variations to moments of buffooning vaudeville, including a dog riding a bicycle (the first bicycle in Russian ballet, thinks Ratmansky) and a man dressed up in Sylphide costume.

Shostakovich’s writing reflected a similar populist balance, with snatches of folk melody and familiar dance numbers elegantly refracted through the score. As Ratmansky says: “They both wanted to make a ballet that was easy to understand, but of a very high quality.” And when The Bright Stream was premiered in Leningrad, the two men thought they had succeeded. Not only was every performance sold out but, according to Ratmansky, “All the critics raved about new horizons opening up and about this being the first major success of Soviet ballet.”

The problems arose when The Bright Stream was transferred to Moscow, and became vulnerable to the paranoid scrutiny of those closest to the Kremlin. Lopukhov had guessed in advance that he would have to make a few discreet changes, including cutting out the man in the Sylphide frock, which he suspected could be a cross-dressing joke too far. But it seems that the ballet was marked out as a scapegoat even before it arrived.

One of its main offences was simply to be composed by Shostakovich. “Clouds were already hanging over the composer,” says Ratmansky. “Stalin had hated his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, and he had a lot of rivals who wanted him brought down.” But the ballet was equally imperilled by its attempt at socialist realism. At that time, no one had yet formulated strict — and safe — guidelines as to what that genre entailed. Lopukhov may have thought that putting farm workers on pointe was a stroke of politically correct genius, but his enemies decided to interpret it as an act of bourgeois false consciousness.

Immediately after the Moscow premiere, an editorial in Pravda condemned Lopukhov and Shostakovich as “slick and high-handed” fakes who had insulted the Russian farmers by representing them as “sugary paysans from off a pre-revolutionary chocolate box”. Rather than having studied the real “way of life” on a collective farm, and respected the real “folk songs, folk dances and games” of their comrades, they had produced a work that indulged the worst crimes of Soviet art, “coarse naturalism and aesthetic formalism”. Given the true state of Russian agriculture, the party ought to have been grateful for the ballet’s tact.

It was only the tragic co-librettist, Piotrovsky, who suffered physically in the gulag, but the professional consequences for the other two were devastating. Shostakovich never wrote another ballet score (his 1975 work, The Dreamers was almost entirely cobbled together out of previous material). And Lopukhov (who may have been saved from the gulag by the fact that his ballerina sister Lydia was married to the celebrated British economist John Maynard Keynes) not only had his appointment as director of the Bolshoi Ballet stripped from him, but during the remaining 37 years of his career would choreograph only a handful of works, mostly for ballet students.

For Ratmansky, the act of rehabilitating Lopukhov was very important. “The richness of his ideas, his courage in using contemporary stories in ballet, are still a real source of inspiration,” he says. Even though he could do nothing to restore the original choreography of The Bright Stream, which was never notated, in 2003 he created a new version, working from Lopukhov’s libretto, which was, he says, “brilliantly detailed, brilliantly constructed with the music”. Those who have seen the ballet feel he has captured some essence of the original, something that matters to Ratmansky not just for Lopukhov’s sake but also for the Bolshoi’s. “These days so many companies look the same, it is hard to have an individual style and identity,” he says. “But Soviet ballets like The Bright Stream, no one else has them. They are unique to us. We need to treasure them”.

The ballet aimed to satisfy the interests and ideas of the new government and implement its slogans, in particular, the slogan about erasing the line between the art of professionals and amateur performances. The action takes place on the collective farm "The Bright Stream" located in the North Caucasus, where collective farmers, amidst an abundance of growing fields, merrily completing their simple agricultural work, dance and perform on stage with professional artists. Such a direct illustration of the Soviet slogan could be regarded as a sharp satirical pamphlet.

Alexei Ratmansky, currently an artist in residence at the American Ballet Theatre and the former director of the Bolshoi Ballet, first came across the full score of the ballet in a recording made by Gennady Rozhdestvensky in Stockholm in 1995. Unable to restore the original choreography of the ballet, which was never notated, Ratmansky wrote his own choreography and staged the new version of The Limpid Stream with the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow in 2003.

In July 2005 the Bolshoi performed The Bright Stream at the Met, and in August 2006, at the Royal Opera House, London. The Bolshoi is performing it in Moscow during late October 2017.

In January 2011, American Ballet Theatre performed The Bright Stream in Ratmansky's choreography, at the Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C..

Teatralnaya Square 1

Teatralnaya Square 1