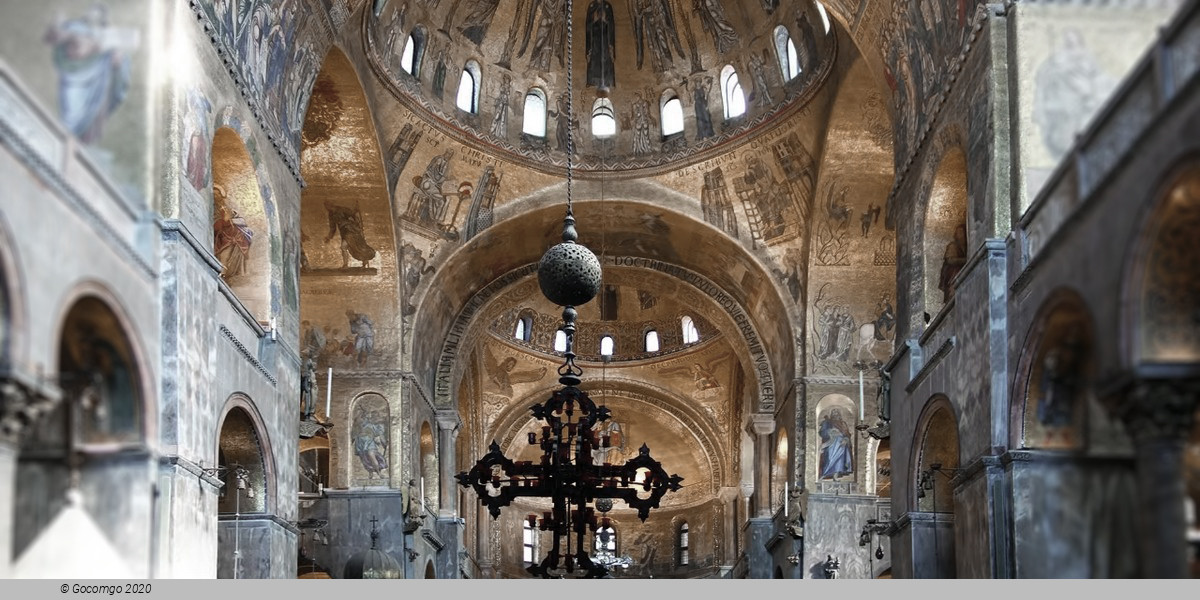

St. Mark’s Basilica (Venice, Italy)

St. Mark’s Basilica

St. Mark’s Music Chapel was born at the beginning of the 14th century and very soon it becomes the centre of Venetian musical life, where style and ways of considering music suited to the magnificence of the Basilica developed. At the second half of the 16th century a new musical thought evolved leading to a radical change that influenced the centuries that followed. In the period when the greatest Renaissance composers actively took part in the Chapel’s life (Willaert, Merulo, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, and Monteverdi), “broken choirs“, echo sonatas – the instrumental parts with melodic lines not the same as the choral lines – were born in the Basilica, a new way of connecting music and word defines and with the aid of new instrumental techniques a new conception of the sound evolves.

The history of St. Mark’s music chapel reflects the evolutions of Venetian civilisation to a large extent.

Following the basilica’s consecration (1094), the “first musical era” was characterised by the presence of fourteen organists. Between 1489 and 1490 two organists, Fra Urbano and Francesco Dana, marked the “second musical era” with their inauguration of the portative organ. The figure of the Chapel Maestro, Pietro de Fossis, was soon added, which started the so-called “third musical era“.

The chant school was given to Adriano Willaert upon the death of the Flemish maestro. Among Willaert’s best pupils were Cipriano de Rore, Gioseffo Zarlino, Costanzo Porta and Claudio Merulo.

A highly innovative thrust came from composers of Venetian origin, Baldassarre Donato and Andrea Gabrieli, considered to be the founders of the so-called “Venetian school”, which became the new reference point in European music. Their passage was deepened by the famous “Young” triplet: Gabrieli, the nephew of Andrea, Bassano and Croce, who gave voice and sound to the moment of greatest splendour in Venetian civilisation.

The “fourth musical era” reached its maximum splendour with Claudio Monteverdi, one of the greatest musical geniuses. Together with his pupils, mainly Giovanni Rovetta and Francesco Cavalli and his collaborators, Alessandro Grandi and Francesco Usper, Monteverdi’s name went well beyond the confines of the Republic.

The “fifth era” was marked by the presence of composers in the basilica trained by Antonio Lotti and Baldassarre Galuppi who continued to ubiquitously diffuse the Venetian musical inspiration with their compositions.

When the “Serenissima” fell (1797) the Chapel saw its leadership in the European panorama become drastically reduced but without losing its continuity. The XIX century, in which we can say the last period began, was passed under the guidance of maestros Giovanni Perotti, Antonio Buzzolla, Venetian Nicol� Cocconand finally the young Lorenzo Perosi who would strongly influence the XX century productions. In 1974 the Chapel risked total paralysis due to the dissolution desired by the Procurator of the same basilica. Only the constancy and goodwill of the singers, still present today, and that of Alfredo Bravi and Roberto Micconihave permitted the chapel to survive.

In addition to the organ, also other instruments were used during solemn feasts in the basilica in the first half of the 16th century. However, they did not have a stable role in liturgical functions but were instead only used on special occasions. It was only starting in the second half of the 16th century that they acquired a fixed, official role.

The participation of instruments in liturgical music is widely certified, and St. Mark’s Basilica’s predilection for wind instrument groups is also copiously documented.

Choristers were also musicians at the end of the 15th century and beginning of the 16th century so if it was necessary, instead of performing the part vocally, they were able to play it similarly.

In his explanations preceding his 1587 “Concerti“, Giovanni Gabrieli wrote of “Musiche proportionate a voci, et Stromenti, come oggidi s’usa nelle principali Chiese de Principi, et nelle Academie illustri” (“Music proportioned to voices and instruments, as is used today in the leading churches of princes and in the distinguished academies”), from which it is legitimate to deduce that the use of instruments in the liturgical service depicts a novelty restricted to the most important churches.

A purely instrumental execution is never mentioned in the documents. In fact, all the elements lead us to think the instruments were used to support the voices or that there was a mixed vocal and instrumental ensemble.

In Gentile Bellini‘s famous painting, Procession della Croce in piazza di San Marco (Procession in St. Mark’s Square), groups of wind instrumentalists are portrayed with cornets and trombones, a vocal group with an arm viol player and a lute-player. The organ naturally could not be used in processions and this consequently helped the instrumental group’s execution. The participation of wind instruments on these occasions is not documented in the records of St. Mark’s registers since the contracts were often drawn up orally.

The executions in religious music outdoors were always mixed – vocal and instrumental – and so the use of musical forms only for instruments, such as the ricercares and those relative to them, is to be ruled out. Like the canzon da sonare (song to be played) and the capriccios, ricercares are essentially chamber forms intended for a small audience. Their nature derives from the very pleasure of the musicians. Afterwards, as is commonly said, one went “from the chamber to the church”, hence to a larger, more spacious environment, and the new compositions were affected by the interlocutor’s change.

Numerous instrumental combinations, sound effects and great formal architectures were tested in St. Mark’s. Powerful wind instruments were selected in various groups of our or five parts and were often countered to each other. The ensembles communicated, blended together and contrasted each other in different combinations. At times the parts reached very numerous groupings. Also, string instruments were introduced on a few occasions, though in small numbers and rarely with lutes as well. The conflicts intensified and the oppositions of the choirs grew in order to obtain a colouristic interplay projected towards maximum splendour.

The choice of the instruments and voices depended on the type of songs to be performed. Not only were vocal and instrumental groups mixed, but voices and instruments were even brought together within the choir itself. Gabrieli‘s “Symphonie Sacrae” of 1615 also could be performed “tam vocibus quam instrumentis“, but here the instruments did not reinforce the voices. They were rather inserted into the dialogue and in many cases carried out an autonomous role. Gabrieli added to polychoral writing without breaking with the past, reaching a new vocal and instrumental sensitivity and forcefully grafting past and contemporary musical experiences. There was no break with the previous tradition, but rather an introduction of new colours, timbres and multiple sound associations.

Thanks to his contribution, the instrumental language finally equalized with the vocal language. After him, instrumental compositions were normally published apart from the vocal production and in an increasingly higher number.

In his wake, instrumental compositions were generally published independently from the vocal production and in an ever-increasing number. Instruments gradually replaced voices and even by the end of the XVII century entirely instrumental forms abounded in the basilica.

Combined choral arrangements survived at S. Marco and fed new works until the fall of the Republic (1797).

An instrumental formation was already active in the sixteenth century at “Palazzo Ducale” and in the basilica on the most important occasions with its own “concert maestro”. This collection of players became an increasingly authentic orchestra within the basilica and was very active until the end of the XIX century.